4.5 Routing Among Mobile Devices

It probably should not be a great surprise to learn that mobile devices present some challenges for the Internet architecture. The Internet was designed in an era when computers were large, immobile devices, and, while the Internet’s designers probably had some notion that mobile devices might appear in the future, it’s fair to assume it was not a top priority to accommodate them. Today, of course, mobile computers are everywhere, notably in the form of laptops and smartphones, and increasingly in other forms, such as drones. In this section, we will look at some of the challenges posed by the appearance of mobile devices and some of the current approaches to accommodating them.

4.5.1 Challenges for Mobile Networking

It is easy enough today to turn up in a wireless hotspot, connect to the Internet using 802.11 or some other wireless networking protocol, and obtain pretty good Internet service. One key enabling technology that made the hotspot feasible is DHCP. You can settle in at a coffee shop, open your laptop, obtain an IP address for your laptop, and get your laptop talking to a default router and a Domain Name System (DNS) server, and for a broad class of applications you have everything you need.

If we look a little more closely, however, it’s clear that for some application scenarios, just getting a new IP address every time you move—which is what DHCP does for you—isn’t always enough. Suppose you are using your laptop or smartphone for a Voice over IP telephone call, and while talking on the phone you move from one hotspot to another, or even switch from Wi-Fi to the cellular network for your Internet connection.

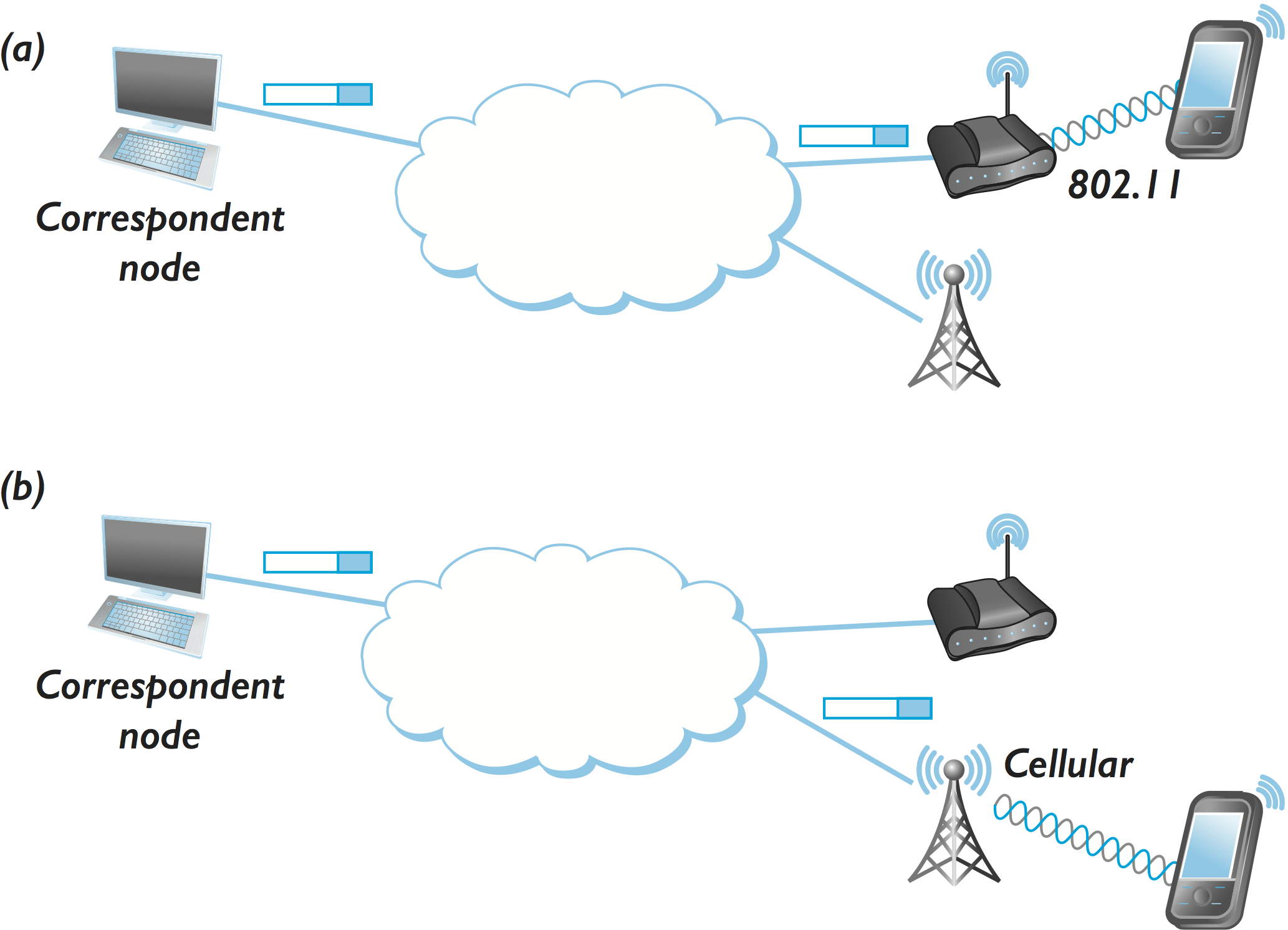

Clearly, when you move from one access network to another, you need to get a new IP address—one that corresponds to the new network. But, the computer or telephone at the other end of your conversation doesn’t immediately know where you have moved or what your new IP address is. Consequently, in the absence of some other mechanism, packets would continue to be sent to the address where you used to be, not where you are now. This problem is illustrated in Figure 122; as the mobile node moves from the 802.11 network in Figure 122(a) to the cellular network in Figure 122(b), somehow packets from the correspondent node need to find their way to the new network and then on to the mobile node.

Figure 122. Forwarding packets from a correspondent node to a mobile node.

There are many different ways to tackle the problem just described, and we will look at some of them below. Assuming that there is some way to redirect packets so that they come to your new address rather than your old address, the next immediately apparent problems relate to security. For example, if there is a mechanism by which I can say, “My new IP address is X,” how do I prevent some attacker from making such a statement without my permission, thus enabling him to either receive my packets, or to redirect my packets to some unwitting third party? Thus, we see that security and mobility are quite closely related.

One issue that the above discussion highlights is the fact that IP addresses actually serve two tasks. They are used as an identifier of an endpoint, and they are also used to locate the endpoint. Think of the identifier as a long-lived name for the endpoint, and the locator as some possibly more temporary information about how to route packets to the endpoint. As long as devices do not move, or do not move often, using a single address for both jobs seem pretty reasonable. But once devices start to move, you would rather like to have an identifier that does not change as you move—this is sometimes called an Endpoint Identifier or Host Identifier—and a separate locator. This idea of separating locators from identifiers has been around for a long time, and most of the approaches to handling mobility described below provide such a separation in some form.

The assumption that IP addresses don’t change shows up in many different places. For example, transport protocols like TCP have historically made assumptions about the IP address staying constant for the life of a connection, so one approach could be to redesign transport protocols so they can operate with changing end-point addresses.

But rather than try to change TCP, a common alternative is for the application to periodically re-establish the TCP connection in case the client’s IP address has changed. As strange as this sounds, if the application is HTTP-based (e.g., a web browser like Chrome or a streaming application like Netflix) then that is exactly what happens. In other words, the strategy is for the application to work around situations where the user’s IP address may have changed, instead of trying to maintain the appearance that it does not change.

While we are all familiar with endpoints that move, it is worth noting that routers can also move. This is certainly less common today than endpoint mobility, but there are plenty of environments where a mobile router might make sense. One example might be an emergency response team trying to deploy a network after some natural disaster has knocked out all the fixed infrastructure. There are additional considerations when all the nodes in a network, not just the endpoints, are mobile, a topic we will discuss later in this section.

Before we start to look at some of the approaches to supporting mobile devices, a couple of points of clarification. It is common to find that people confuse wireless networks with mobility. After all, mobility and wireless often are found together for obvious reasons. But wireless communication is really about getting data from A to B without a wire, while mobility is about dealing with what happens when a node moves around as it communicates. Certainly many nodes that use wireless communication channels are not mobile, and sometimes mobile nodes will use wired communication (although this is less common).

Finally, in this chapter we are mostly interested in what we might call network-layer mobility. That is, we are interested in how to deal with nodes that move from one network to another. Moving from one access point to another in the same 802.11 network can be handled by mechanisms specific to 802.11, and cellular networks also have ways to handle mobility, of course, but in large heterogeneous systems like the Internet we need to support mobility more broadly across networks.

4.5.2 Routing to Mobile Hosts (Mobile IP)

Mobile IP is the primary mechanism in today’s Internet architecture to tackle the problem of routing packets to mobile hosts. It introduces a few new capabilities but does not require any change from non-mobile hosts or most routers—thus making it incrementally deployable.

The mobile host is assumed to have a permanent IP address, called its home address, which has a network prefix equal to that of its home network. This is the address that will be used by other hosts when they initially send packets to the mobile host; because it does not change, it can be used by long-lived applications as the host roams. We can think of this as the long-lived identifier of the host.

When the host moves to a new foreign network away from its home network, it typically acquires a new address on that network using some means such as DHCP. This address is going to change every time the host roams to a new network, so we can think of this as being more like the locator for the host, but it is important to note that the host does not lose its permanent home address when it acquires a new address on the foreign network. This home address is critical to its ability to sustain communications as it moves, as we’ll see below.

Because DHCP was developed around the same time as Mobile IP, the original Mobile IP standards did not require DHCP, but DHCP is ubiquitous today.

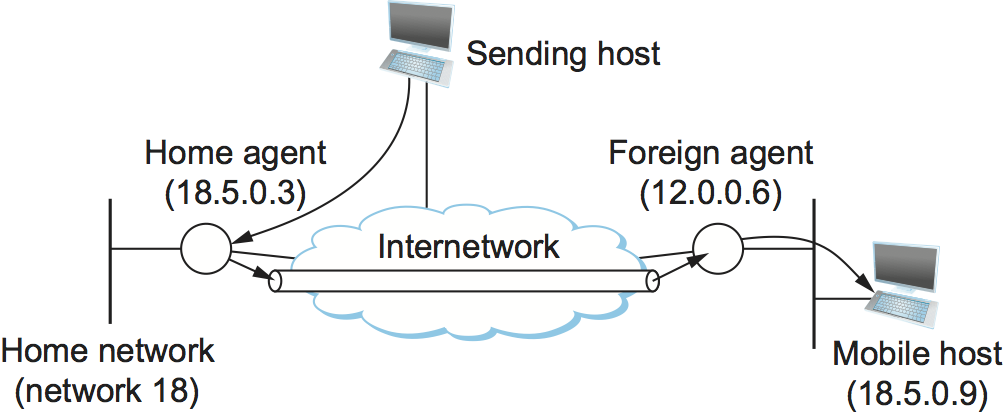

While the majority of routers remain unchanged, mobility support does require some new functionality in at least one router, known as the home agent of the mobile node. This router is located on the home network of the mobile host. In some cases, a second router with enhanced functionality, the foreign agent, is also required. This router is located on a network to which the mobile node attaches itself when it is away from its home network. We will consider first the operation of Mobile IP when a foreign agent is used. An example network with both home and foreign agents is shown in Figure 123.

Figure 123. Mobile host and mobility agents.

Both home and foreign agents periodically announce their presence on the networks to which they are attached using agent advertisement messages. A mobile host may also solicit an advertisement when it attaches to a new network. The advertisement by the home agent enables a mobile host to learn the address of its home agent before it leaves its home network. When the mobile host attaches to a foreign network, it hears an advertisement from a foreign agent and registers with the agent, providing the address of its home agent. The foreign agent then contacts the home agent, providing a care-of address. This is usually the IP address of the foreign agent.

At this point, we can see that any host that tries to send a packet to the mobile host will send it with a destination address equal to the home address of that node. Normal IP forwarding will cause that packet to arrive on the home network of the mobile node on which the home agent is sitting. Thus, we can divide the problem of delivering the packet to the mobile node into three parts:

How does the home agent intercept a packet that is destined for the mobile node?

How does the home agent then deliver the packet to the foreign agent?

How does the foreign agent deliver the packet to the mobile node?

The first problem might look easy if you just look at Figure 123, in which the home agent is clearly the only path between the sending host and the home network and thus must receive packets that are destined to the mobile node. But what if the sending (correspondent) node were on network 18, or what if there were another router connected to network 18 that tried to deliver the packet without its passing through the home agent? To address this problem, the home agent actually impersonates the mobile node, using a technique called proxy ARP. This works just like Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), except that the home agent inserts the IP address of the mobile node, rather than its own, in the ARP messages. It uses its own hardware address, so that all the nodes on the same network learn to associate the hardware address of the home agent with the IP address of the mobile node. One subtle aspect of this process is the fact that ARP information may be cached in other nodes on the network. To make sure that these caches are invalidated in a timely way, the home agent issues an ARP message as soon as the mobile node registers with a foreign agent. Because the ARP message is not a response to a normal ARP request, it is termed a gratuitous ARP.

The second problem is the delivery of the intercepted packet to the foreign agent. Here we use the tunneling technique described elsewhere. The home agent simply wraps the packet inside an IP header that is destined for the foreign agent and transmits it into the internetwork. All the intervening routers just see an IP packet destined for the IP address of the foreign agent. Another way of looking at this is that an IP tunnel is established between the home agent and the foreign agent, and the home agent just drops packets destined for the mobile node into that tunnel.

When a packet finally arrives at the foreign agent, it strips the extra IP header and finds inside an IP packet destined for the home address of the mobile node. Clearly the foreign agent cannot treat this like any old IP packet because this would cause it to send it back to the home network. Instead, it has to recognize the address as that of a registered mobile node. It then delivers the packet to the hardware address of the mobile node (e.g., its Ethernet address), which was learned as part of the registration process.

One observation that can be made about these procedures is that it is possible for the foreign agent and the mobile node to be in the same box; that is, a mobile node can perform the foreign agent function itself. To make this work, however, the mobile node must be able to dynamically acquire an IP address that is located in the address space of the foreign network (e.g., using DHCP). This address will then be used as the care-of address. In our example, this address would have a network number of 12. This approach has the desirable feature of allowing mobile nodes to attach to networks that don’t have foreign agents; thus, mobility can be achieved with only the addition of a home agent and some new software on the mobile node (assuming DHCP is used on the foreign network).

What about traffic in the other direction (i.e., from mobile node to fixed node)? This turns out to be much easier. The mobile node just puts the IP address of the fixed node in the destination field of its IP packets while putting its permanent address in the source field, and the packets are forwarded to the fixed node using normal means. Of course, if both nodes in a conversation are mobile, then the procedures described above are used in each direction.

Route Optimization in Mobile IP

There is one significant drawback to the above approach: The route from the correspondent node to the mobile node can be significantly suboptimal. One of the most extreme examples is when a mobile node and the correspondent node are on the same network, but the home network for the mobile node is on the far side of the Internet. The sending correspondent node addresses all packets to the home network; they traverse the Internet to reach the home agent, which then tunnels them back across the Internet to reach the foreign agent. Clearly, it would be nice if the correspondent node could find out that the mobile node is actually on the same network and deliver the packet directly. In the more general case, the goal is to deliver packets as directly as possible from correspondent node to mobile node without passing through a home agent. This is sometimes referred to as the triangle routing problem since the path from correspondent to mobile node via home agent takes two sides of a triangle, rather than the third side that is the direct path.

The basic idea behind the solution to triangle routing is to let the correspondent node know the care-of address of the mobile node. The correspondent node can then create its own tunnel to the foreign agent. This is treated as an optimization of the process just described. If the sender has been equipped with the necessary software to learn the care-of address and create its own tunnel, then the route can be optimized; if not, packets just follow the suboptimal route.

When a home agent sees a packet destined for one of the mobile nodes that it supports, it can deduce that the sender is not using the optimal route. Therefore, it sends a “binding update” message back to the source, in addition to forwarding the data packet to the foreign agent. The source, if capable, uses this binding update to create an entry in a binding cache, which consists of a list of mappings from mobile node addresses to care-of addresses. The next time this source has a data packet to send to that mobile node, it will find the binding in the cache and can tunnel the packet directly to the foreign agent.

There is an obvious problem with this scheme, which is that the binding cache may become out-of-date if the mobile host moves to a new network. If an out-of-date cache entry is used, the foreign agent will receive tunneled packets for a mobile node that is no longer registered on its network. In this case, it sends a binding warning message back to the sender to tell it to stop using this cache entry. This scheme works only in the case where the foreign agent is not the mobile node itself, however. For this reason, cache entries need to be deleted after some period of time; the exact amount is specified in the binding update message.

As noted above, mobile routing provides some interesting security challenges, which are clearer now that we have seen how Mobile IP works. For example, an attacker wishing to intercept the packets destined to some other node in an internetwork could contact the home agent for that node and announce itself as the new foreign agent for the node. Thus, it is clear that some authentication mechanisms are required.

Mobility in IPv6

There are a handful of significant differences between mobility support in IPv4 and IPv6. Most importantly, it was possible to build mobility support into the standards for IPv6 pretty much from the beginning, thus alleviating a number of incremental deployment problems. (It may be more correct to say that IPv6 is one big incremental deployment problem, which, once solved, will deliver mobility support as part of the package.)

Since all IPv6-capable hosts can acquire an address whenever they are attached to a foreign network (using several mechanisms defined as part of the core v6 specifications), Mobile IPv6 does away with the foreign agent and includes the necessary capabilities to act as a foreign agent in every host.

One other interesting aspect of IPv6 that comes into play with Mobile IP is its inclusion of a flexible set of extension headers, as described elsewhere in this chapter. This is used in the optimized routing scenario described above. Rather than tunneling a packet to the mobile node at its care-of address, an IPv6 node can send an IP packet to the care-of address with the home address contained in a routing header. This header is ignored by all the intermediate nodes, but it enables the mobile node to treat the packet as if it were sent to the home address, thus enabling it to continue presenting higher layer protocols with the illusion that its IP address is fixed. Using an extension header rather than a tunnel is more efficient from the perspective of both bandwidth consumption and processing.

Finally, we note that many open issues remain in mobile networking. Managing the power consumption of mobile devices is increasingly important, so that smaller devices with limited battery power can be built. There is also the problem of ad hoc mobile networks—enabling a group of mobile nodes to form a network in the absence of any fixed nodes—which has some special challenges. A particularly challenging class of mobile networks is sensor networks. Sensors typically are small, inexpensive, and often battery powered, meaning that issues of very low power consumption and limited processing capability must also be considered. Furthermore, since wireless communications and mobility typically go hand in hand, the continual advances in wireless technologies keep on producing new challenges and opportunities for mobile networking.